Coexisting with wild animals

Raccoons may establish a toilet or “latrine” site in backyards. Raccoons are not carriers of rabies in B.C., but their poop may contain raccoon roundworm eggs that can be dangerous to people and pets. Try using motion-sensor lights or sprinklers to prevent raccoons from using your backyard as a toilet.

To clean raccoon poop on your property:

Avoid direct contact with the feces, and wear gloves and a face mask for protection. Scoop the feces up using a plastic bag or shovel, close tightly and place in the garbage.

Use heat to kill roundworm eggs:

- Use boiling water to destroy any roundworm eggs on every surface or item that touched the feces.

- If you can’t use boiling water on the surface or item, using a 10% bleach solution will dislodge roundworm eggs so they can be rinsed away.

- Flaming with a propane torch is also effective, but use with caution to avoid injury, damage, or starting a fire. Do not attempt to flame any surfaces that could melt or catch fire, and check the regulations of your local fire department and municipality in advance.

More information on cleaning raccoon latrines (CDC).

If you need help getting a raccoon out of your house, call an AnimalKind company. For more information on managing raccoons, read or print our best practices (PDF).

The BC SPCA can’t stop a legally-permitted cull from happening in your community. However, the BC SPCA can intervene if the killing methods are inhumane (by law) or if animals are in distress. If you witness an animal in distress during a cull, call our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722. Document evidence by taking videos or photos, but do not trespass on private property or put yourself in danger.

The BC SPCA is opposed to culling animals when there is no evidence to support it, or it can’t be done humanely. The BC SPCA’s primary approach to wildlife conflicts is coexistence, and changing human behaviour to prevent problems. International and BC SPCA experts agree there are many steps that must first be taken to justify ethical wildlife control.

Deer culls

The BC SPCA recommends using non-lethal strategies to solve human-deer conflict. Communities should aim to prevent conflict by educating residents about coexisting with urban deer. Culling is an inefficient, short-term solution and should not be a default practice.

Read our position statement on urban deer.

Download our urban deer pamphlet (PDF).

Geese and other bird culls

The BC SPCA recommends hazing and environmental modifications to prevent conflicts with birds, as well as providing education that discourages feeding by the public. When appropriate, fertility control is a non-lethal way to limit reproduction, though permits are generally required.

Read our best practice sheets for:

Wolf culls

Wolf culls in B.C. and Alberta have drawn significant criticism. Experts criticize the inhumane methods and lack of evidence that killing wolves will save caribou or other species. Culling can break up wolf pack structures and create an imbalance with other species in the area. Even with skilled shooters, shooting wolves from helicopters can cause stress and death may not be quick and painless.

Read our position statement on predator control.

Ethical considerations for wild animals

Though some are still skeptical, evidence that fish can feel pain has been growing for decades. It has now reached a point where the sentience of fish (their ability to perceive, experience and feel) is acknowledged by leading scientists and organizations around the world. For instance:

“…there is as much evidence that fish feel pain and suffer as there is for birds and mammals…”

– Dr. Victoria Braithwaite, author of Do Fish Feel Pain?

“The evidence of pain and fear system function in fish is so similar to that in humans and other mammals that it is logical to conclude that fish feel fear and pain. Fish are sentient beings.”

– Dr. Donald Broom, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge

“…it would be impossible for fish to survive as the cognitively and behaviourally complex animals they are without a capacity to feel pain.”

– Dr. Culum Brown, editor of The Journal of Fish Biology

“…the preponderance of accumulated evidence supports the position that finfish should be accorded the same considerations as terrestrial vertebrates in regard to relief from pain.”

– American Veterinary Medical Association

Like other animals, fish respond to painful events with changes in their behaviour and physiology. While the parts of their brain involved in the pain response are not anatomically the same as in mammals, for example, their function is very similar. Pain teaches fish to avoid things that cause them harm, helping them to respond effectively to their environment and, ultimately, to survive.

Classrooms are an unnatural and stressful setting for wild or exotic animals. Seeing these animals outside of their natural wild habitat does not provide educational benefits and will likely lead to their early death.

Also, wild and exotic animals can carry diseases that may be passed onto children, who are still developing their immune systems.

There are many ways to experience and appreciate wild and exotic animals in nature, online or through documentaries. Compassion starts young, so let’s keep animals in nature.

Read our positions on animals in schools, educational visits using animals, exotic pets and wildlife welfare.

Research suggests that lobsters (along with other decapod crustaceans such as crabs) have the capacity to feel pain. While some believe the science is inconclusive, others consider the evidence as strong as the evidence for pain in fish.

The BC SPCA believes that it is best to err on the side of caution by avoiding potentially painful practices such as boiling these animals alive. Instead, we recommend that lobsters be humanely killed by trained and competent personnel before purchase. Humanely killing a lobster is typically a two-step process: the animal is first rendered insensible (incapable of feeling pain) before being killed.

As an animal welfare organization, the BC SPCA acknowledges that recreational fishing for food and for sport is an important activity to many Canadians.

We believe that recreational fishing — like hunting — should be carried out in an ethical, humane, responsible and sustainable manner by qualified and experienced anglers, who abide by applicable laws and regulations. The best possible angling practices and handling methods that minimize stress should be employed, together with the use of gear that causes the least amount of injury and pain.

When fish are caught to be eaten, they should be killed humanely. The handling methods and equipment used should ensure that fear and pain are kept to absolutely minimal levels prior to and during killing.

When catching and releasing fish, anglers should take into account how much the fish is likely to suffer, and how likely the fish is to survive. Ultimately, catch-and-harvest may be preferable to catch-and-release, given how poorly fish can fare after they are released. Studies have shown that, depending on the species and method of capture, post-release mortality can range from 0 to 95 per cent.

NOTE: The BC SPCA’s Wild ARC is NOT currently able to accept fur coat donations.

The sad facts about fur are hard to ignore, and many people are looking to make their home more fur-free. Sometimes this is as small as fur trim on a sweater, hat, or other accessory, or sometimes it’s an entire coat inherited from a family member. If you want to re-purpose or re-home old furs, consider these options:

Remove fur trim

Simply removing the fur is the easiest way to reclaim your clothes. Enlist the help of a local tailor for more complicated projects that might require expert removal and repair. Ask to keep any fur trimmings so you can ensure they stay out of the fashion industry.

Donate fur

The BC SPCA is frequently contacted from people wishing to donate their fur coats to Wild ARC and other wildlife rehabilitation centres. This has been so successful over the last few years that many now have an overabundance of furs! Unfortunately, furs can’t be cleaned the same way as other textiles – for the safety of our patients, they have to be discarded once soiled. Please note Wild ARC is NOT currently able to accept fur donations.

Research and consider donating to local animal protection groups or museums, who sometimes have educational uses for fur.

Communities living in the Arctic may also have a need for fur donations. Fur is considered a necessity in this part of Canada, where temperatures can drop below zero for nine months of the year and can get as cold as -65C with the windchill. Fur and leather are also very expensive in the Arctic, so donating fur coats is a positive way to support northern communities.

Fur burial

For some people, simply laying the fur to rest is one way to find peace. Find somewhere acceptable to hold a small ceremony and bury the fur, first removing any synthetic components.

How to help wild animals

Yes, some school programs will give you credit for volunteering with the BC SPCA.

Practicums at Wild ARC are available for university and professional training credits.

Practicums at the Vancouver Branch are also available to university students if registered through the University of British Columbia.

High-school work experience may also be available at your local BC SPCA branch. Contact them directly for details.

Veterinary and registered animal health technologist externships may also be available at certain BC SPCA Hospitals and Clinics. Contact them directly for details.

After ducklings and goslings hatch, their parents walk the babies (who can’t fly yet) to nearby water sources. Sometimes the families get stuck at road medians if they try to cross a highway or busy street. This creates a tricky situation where both the animals and the rescuers might be in danger. Trying to herd the family can cause them to panic and run into traffic, and rescuers may disrupt traffic or risk their own safety.

The best way to help duck or geese families trying to cross the street is to contact local police for help stopping traffic. Once traffic is stopped, slowly and calmly herd the babies and parents to safety. Only try to capture the family if necessary for their safety. If the parents (or babies) panic and scatter, the rescue and reunion can become complicated.

Call our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for help with wildlife issues, including advice on how best to help duck or goose families.

Baby ducks and geese can usually make their own way down from a nest on a roof. But, they may need your help if:

- The building is more than six meters (two storeys) in height

- There is a barrier higher than 13 cm preventing them from hopping down

- The ground below is concrete, cement or other hard material

In any of the above cases, call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 to help you develop a rescue plan.

I found a...

Bats are the only wild carrier of rabies in B.C. and should never be touched or directly handled. Rabies can spread through just a drop of a bat’s saliva. Vaccinate your pet to protect them from contracting rabies.

If a bat has had any skin contact with a person, the bat must be euthanized and tested for rabies. If a bat has had contact with a pet, the bat may be sent for rabies testing. Contact your doctor, veterinarian or local public health authority immediately in cases of contact with a bat. Learn more about rabies transmission.

Bat populations are in decline, and injured bats can be rehabilitated. Call your local wildlife rehabilitator or our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice on safely containing bats.

Help bats by also watching out for signs of White-Nose Syndrome (WNS). White-Nose Syndrome is a fungal disease that has been devastating bat populations across North America. The fungus grows on the nose and bodies of infected bats during hibernation and causes them to wake and use valuable energy at a time when they should be conserving it. White-Nose Syndrome has not been observed in B.C. yet, but the fungus that causes it was detected in the Grand Forks area in 2023.

Between November 1 and May 31, White-Nose Syndrome can be detected on dead bats if they are infected. Help detect White-Nose Syndrome by reporting dead bats and unusual winter bat activity to the BC Community Bat Program at 1-855-9BC-BATS (922-2287) or by email at info@bcbats.ca.

To learn more about coexisting with bats, read the BC SPCA’s best practices for bats.

Small deceased wild animals found on private property can be buried or bagged and put in the garbage. Do not touch dead wildlife with your bare hands – use disposable gloves or a tool – and never put a dead animal in compost or green bins. For larger animals on private property, it may be your responsibility to dispose of them, and you may need to contact a waste removal company for help. Contact your local municipality for more information.

For deceased animals found on public land, contact your local animal control or public works office for removal.

If there is more than one deceased animal in the same area, or if you suspect disease, consult the provincial government website for reporting instructions for a variety of species including amphibians, bats, birds, small mammals, large mammals, and marine mammals.

Dead bird reporting

Birds are susceptible to diseases such as West Nile virus and avian influenza. To monitor bird health in British Columbia, reports of sick and dead wild birds are of interest to federal and provincial government agencies. The B.C. Wild Bird Mortality Investigation Protocol & Avian Influenza Surveillance Program coordinates the surveillance of diseases and deaths throughout the province.

Report sightings of dead wild birds by reading the Wild Bird Mortality & Avian Influenza Surveillance Program (PDF) information sheet and calling 1-866-431-BIRD (2473).

Sick or injured birds should be taken to a permitted wildlife rehabilitation centre as soon as possible. Read more about how to rescue a wild animal. Still need help? Contact your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice about how to help sick or injured birds.

Learn more about HPAI and ways to reduce transmission in your own backyard.

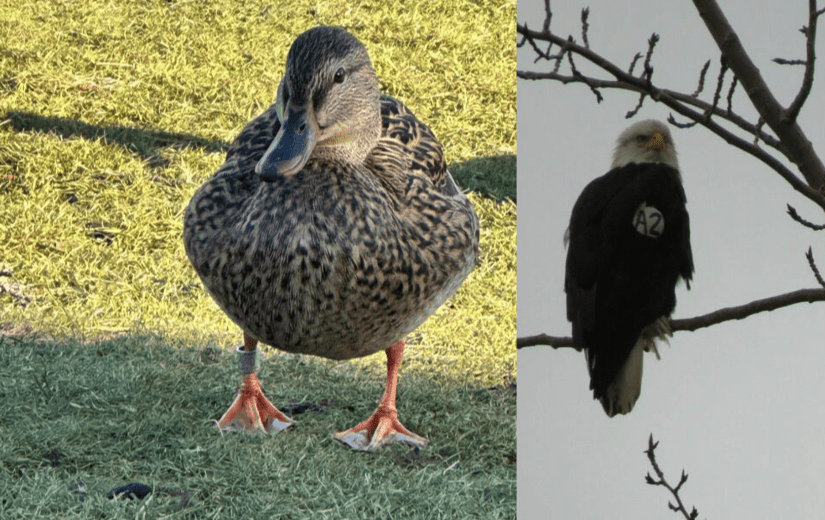

Bird bands

If you find a dead bird with a band or coloured markers, record the letters and numbers and contact the Wild Bird Mortality & Avian Influenza Surveillance Program at 1-866-431-BIRD (2473).

The North American Bird Banding Program collects information on the distribution and movement of species to help wildlife scientists monitor and conserve migratory bird populations. You can contribute by also reporting the band number online at reportband.gov or by calling 1-800-327-BAND (2263) toll-free to leave a message.

Pigeons are not banded as part of the North American Bird Banding Program. A pigeon with a leg band is likely a domestic pigeon and their band will have letters representing a racing association who can help to get in touch with the owner. Learn more about bird banding.

Know your wild neighbours

It is typically illegal to disturb a bird’s nest with eggs or chicks inside. The best solution is to wait a few weeks until the babies grow up. If there is a nest in an area that causes problems (above a building entrance, in a vent) you may need a permit from Environment Canada to move the nest legally.

For species-specific information on managing birds, read our best practices. If you have more questions about a nest of birds, call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice.

Seeing a bear from a safe distance can be a thrilling experience, but what do you do in a surprise encounter with a bear?

Bears are omnivores that eat mostly berries and fish. Their habitats often overlap with ours in places like parks, resorts, hiking trails, or simply our backyards. Bear attacks are very rare – most of the time, they are happy to go unseen by people and will move along on their own. They can lose their healthy fear of people if we’re not careful with our food and garbage, or they may feel threatened if people come too close to their babies.

If you encounter a bear in the wild or in the city, remember to:

- Stay calm and back away slowly – do not run, climb a tree or make any sudden movements or loud noises, back away and give the bear plenty of space so they can move on

- Never feed a bear – bears used to being fed by humans can lose their fear of people and lead to unwanted conflicts and aggression

- Make yourself look big – stand tall or stay together in a group, do not kneel down

- Keep children and pets close – pick up small children and pets so you know where they are while watching the bear

- Don’t make eye contact with the bear – they may see this as a threat or a challenge

- Move indoors – if possible, move indoors and bring children and pets with you

- Report aggressive or threatening encounters by calling the Conservation Officer Service at 1-877-952-7277

Mother bears are protective of their young, so do not approach a baby bear, as mom will be watching from close by. Never try to out-run a bear or climb trees to escape.

Read more about living with bears in B.C.

Black bears vs. grizzly bears

B.C. is home to two kinds of bears – black bears and grizzly bears. Despite their name, black bears can be black, brown, silver, cinnamon or even white (called “Kermode” or “spirit” bears). They are adept tree climbers with large ears, short claws, a long nose, and don’t have a shoulder hump like grizzly bears. Black bears are the most common type of bear near B.C.’s largest cities.

Grizzly bears are sometimes called brown bears, but they can also be black, brown, or blond. They have relatively small ears, long claws, a dish-shaped face, and have a distinct shoulder hump. Grizzly bears generally live in rural and remote areas of B.C. and thrive in undisturbed habitats.

Ducks sit on their nest for three to four weeks before the babies hatch. To prevent the babies from hopping into the pool, cover the pool a few days before you expect the babies will hatch. The babies are small and don’t have waterproof feathers, so they can get hypothermia or drown if left in the water.

If a baby duck or goose ends up in your pool:

- Toss floating objects, like flutterboards, in the pool immediately to give babies temporary resting places

- Make a ramp using foam pool floats, patio chair cushions, or a wooden plank. You can use an empty pop bottle tied to the underside to help it float

- Use a pool skimmer to herd babies towards ramps, but don’t chase them. Chasing causes more stress and will exhaust the babies

- Open the gates to the pool area so the family can move out and find a better water source

If you need further advice on a nesting duck or goose family, call our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722.

Crows and ravens can be hard to tell apart, especially from far away. Crows are smaller than ravens – they have a wingspan of about 92 cm, compared to a raven’s 117 cm.

Crows

Smaller, straight beak

Fan-shaped tail

Characteristic “caw”

~92 cm wingspan

Ravens

Large, thick, rounded beak

Diamond-shaped tail

Deeper “croak”

~117 cm wingspan

Photo by Tony Pace