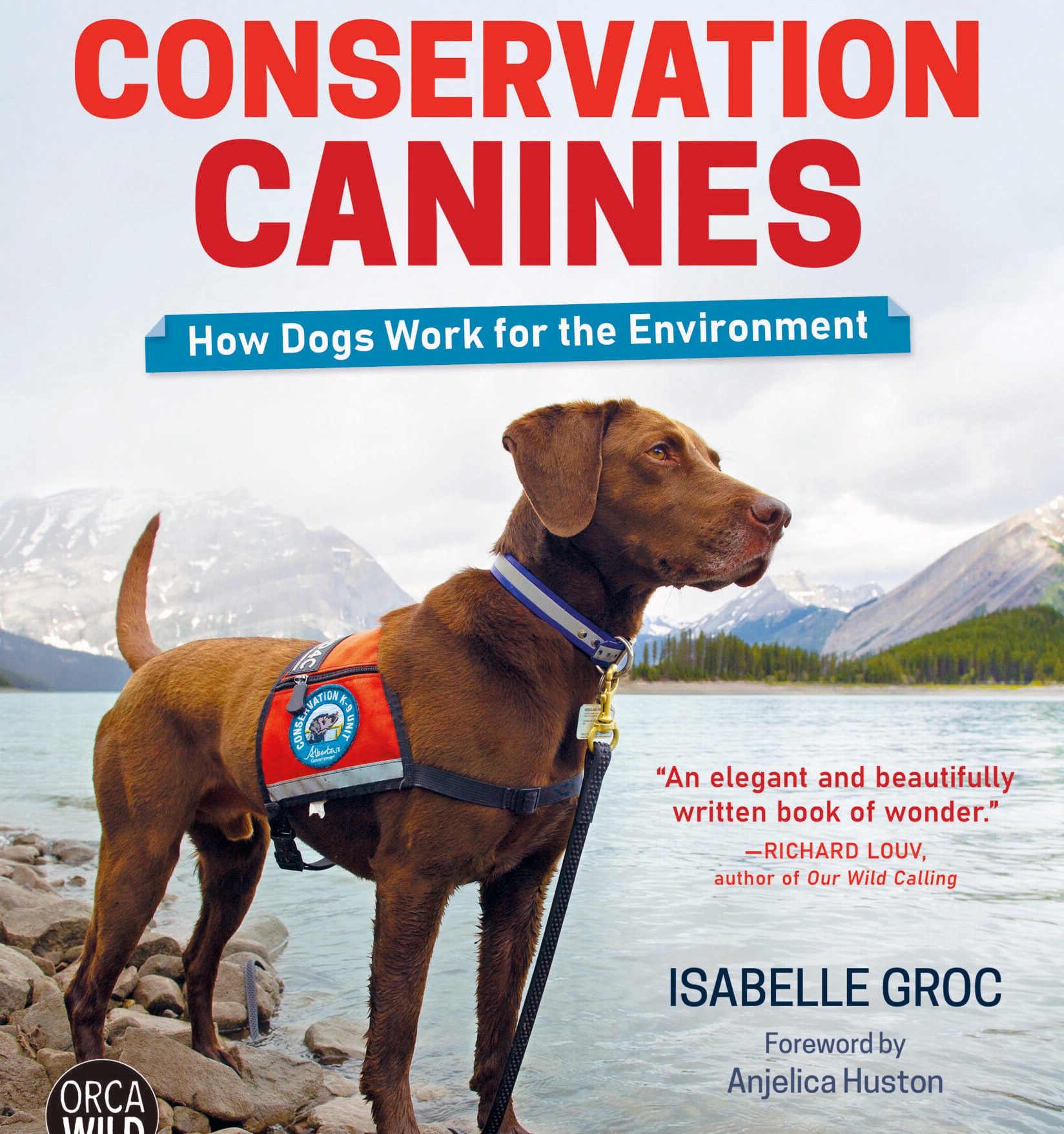

You may have heard of “sniffer dogs” trained to detect bombs or find missing people, but did you know that dogs are also trained to help other animals? In her book Conservation Canines, Isabelle Groc shares examples of how wildlife experts use the power of a dog’s nose to help endangered animals – including here in British Columbia.

Alli and the Oregon spotted frog

British Columbia’s Fraser Valley is home to one of Canada’s most endangered amphibians. The Oregon spotted frog’s numbers are declining rapidly due to the loss of their wetland habitat to human development.

Conservation biologist Monica Pearson’s job is to find Oregon spotted frogs to help protect them. It isn’t easy. The frogs are well camouflaged, and they tend to hide underwater and in tunnels. Plus, walking through knee-deep muddy frog habitat is a slow go.

But not for Alli, an Australian cattle dog and Conservation Canine. Light on her four paws, Alli can cover ground quickly. And her keen nose is trained to sniff out the hard-to-find species.

Monica works with Alli through her trainer, Heath Smith. When Heath sends Alli off to seek frogs, she searches intently. When she stops, lays down and gives Heath a certain “look,” Heath knows Alli has found an Oregon spotted frog.

Monica records the frog’s location and condition. She then attaches a small transmitter belt, so she can track where the frog goes. Alli, meanwhile, enjoys a game of fetch with Heath as her reward.

Pips and the elusive ermine

Before he became a Conservation Canine, Pips was a shelter dog in need of a home. The energetic Australian cattle dog was adopted by Heath Smith to serve in the Conservation Canines program.

One of Pips’s missions? To help find a special species of ermine found only in Haida Gwaii, B.C. Designated as “threatened,” Haida Gwaii ermines are a type of weasel. For years, scientists have searched for the animals using all kinds of methods, from live traps to automatic camera stations. Still, few ermine sightings have been recorded.

Before his mission, Pips learns to detect the poop of another type of ermine. Then, together with Heath, and biologist, Berry Wijdeven, Pips spends 16 days hiking 25 different sites for a total of 50 kilometres. It’s a tough job. But in that time, Pips detects 11 samples of Haida Gwaii ermine scat – the first time any has been found. The findings show that there really aren’t many ermine in the area. But the scat also provides important clues to the animals’ diet, health and use of habitat.

Thanks to Pips, Berry and other scientists now have more information they can use to help protect Haida Gwaii ermines.

Dio and the orca poop

Not all scat detection dogs are suited to work on a boat – but Dio is. With strong sea legs and lots of patience, he’s the right dog for the job. Adopted from a shelter in California, this Conservation Canine has worked on a research vessel sniffing out orca whale poop for two seasons.

In recent years, southern resident orcas off the B.C. coast have become endangered. Currently, only 73 remain. Their main food source, salmon (especially Chinook), is declining. Boat traffic and ocean pollution also take a toll.

To help save the orcas, scientists must understand the impact of boats, pollution and lack of food. Collecting tissue samples from orcas is one way scientists learn what foods orcas eat. Yet getting close to orcas is difficult and scares them. Gathering orca poop offers a hands- (and paws-) off option.

But orca poop isn’t easy to see. It’s small and sinks quickly. Luckily, trained detection dogs can smell it more than a kilometre away! Dio works with his handler, Collette Yee, and Dr. Deborah Giles, a marine mammal scientist and the boat’s captain. When his nose finds something, Dio leans over the boat and points his head where to look. Once at the right spot, Deborah scoops up the sample.

Over the years, dogs like Dio have helped gather hundreds of samples. The data helps scientists understand the size and health of the orcas. One thing is for certain: To protect the orcas, action must also be taken to help increase wild salmon populations.

Note: These stories were selected from the book Conservation Canines by Isabelle Groc and adapted by the BC SPCA.