Wildlife

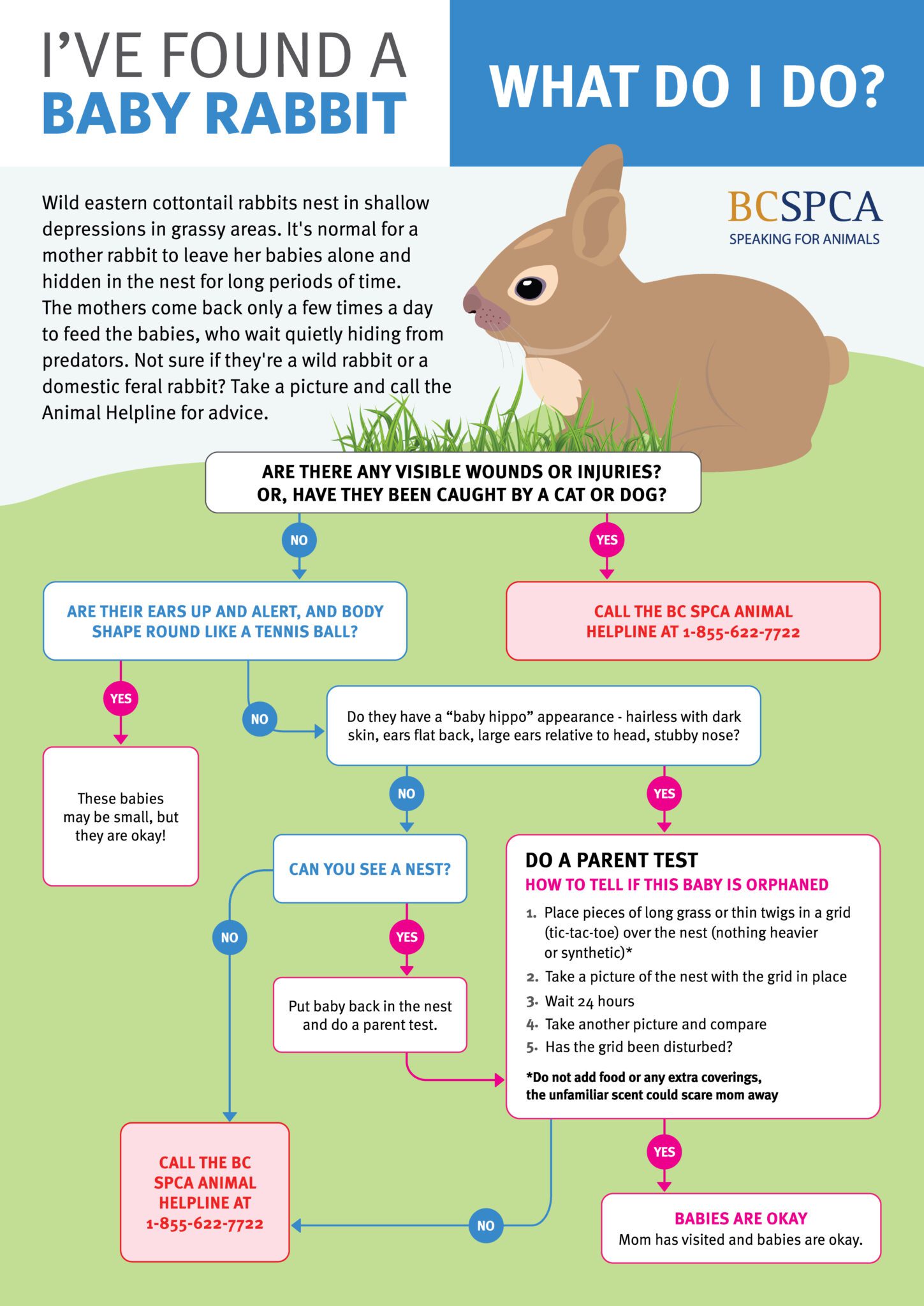

Wild eastern cottontail rabbits nest in shallow depressions in grassy areas, which make baby rabbits vulnerable to lawn-mowers, dogs and free-roaming cats. Baby rabbits found alone don’t always need help – it’s normal for a mother rabbit to leave her babies alone and hidden in the nest for long periods of time. She will typically come back only a few times a day to feed the babies who wait quietly while hiding from predators.

Not sure if they’re a wild rabbit or a domestic feral rabbit? Learn more about telling the species apart or take a picture and call your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice.

Eastern cottontails are born pink and hairless, but develop dark fur very early. They have stubby noses, large ears relative to the size of their head, and their ears lay flat against their body. They have short tails (less than half body length), and front legs shorter than their back legs. All this combined gives eastern cottontail babies the appearance of a “baby hippo”.

A baby rabbit will need help if they:

- have obvious signs of injury (blood, wounds etc.)

- have been caught by a cat or dog

- are orphaned (do a parent test to confirm)

For minor disturbances, babies too young to be on their own can be placed back in the nest with the original nesting material – do a parent test to check that mom has returned. With parental care confirmed, it will only take a couple of weeks for the babies to grow up enough to leave the nest. Keep pets away and hold off on any more yard work until this time. If you’re unsure if they need help, or the babies (and any adults) are obviously injured (e.g., bleeding, broken limbs), call your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice.

Young eastern cottontails may appear very small, but they’re ready to be on their own very quickly!

These rabbits are very close to being able to survive on their own but are still too young to be without a returning parent – their pinned back ears and long bodies are tell-tale signs they still need to be cared for.

This young rabbit is fine to be on their own – their ears are up and alert and their body is round and shaped like a tennis ball.

To find out if a baby rabbit is truly orphaned, do a parent test.

Steps to do a parent test:

- Place pieces of long grass or thin twigs in a grid (tic-tac-toe) over the nest – use natural material rather than synthetic, and do not use heavier materials as the mother rabbit is unlikely to move them during her brief and delicate visits.

- Don’t add anything extra like food or coverings – because rabbits are prey species, new scents may scare the mom from returning, and supplemental food is not necessary and could upset their delicate systems.

- Take a photo of the nest with the grid in place.

- Wait 24 hours.

- Take another photo of the grid and compare it to the first.

- If the grid has been disturbed, the mom has come back to care for her babies. If the grid has not changed, the babies may need to go to a wildlife rehabilitator.

If you are having trouble assessing before and after photos when conducting a parent test, get in touch with your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline for help at 1-855-622-7722.

Read more about rescuing wild animals.

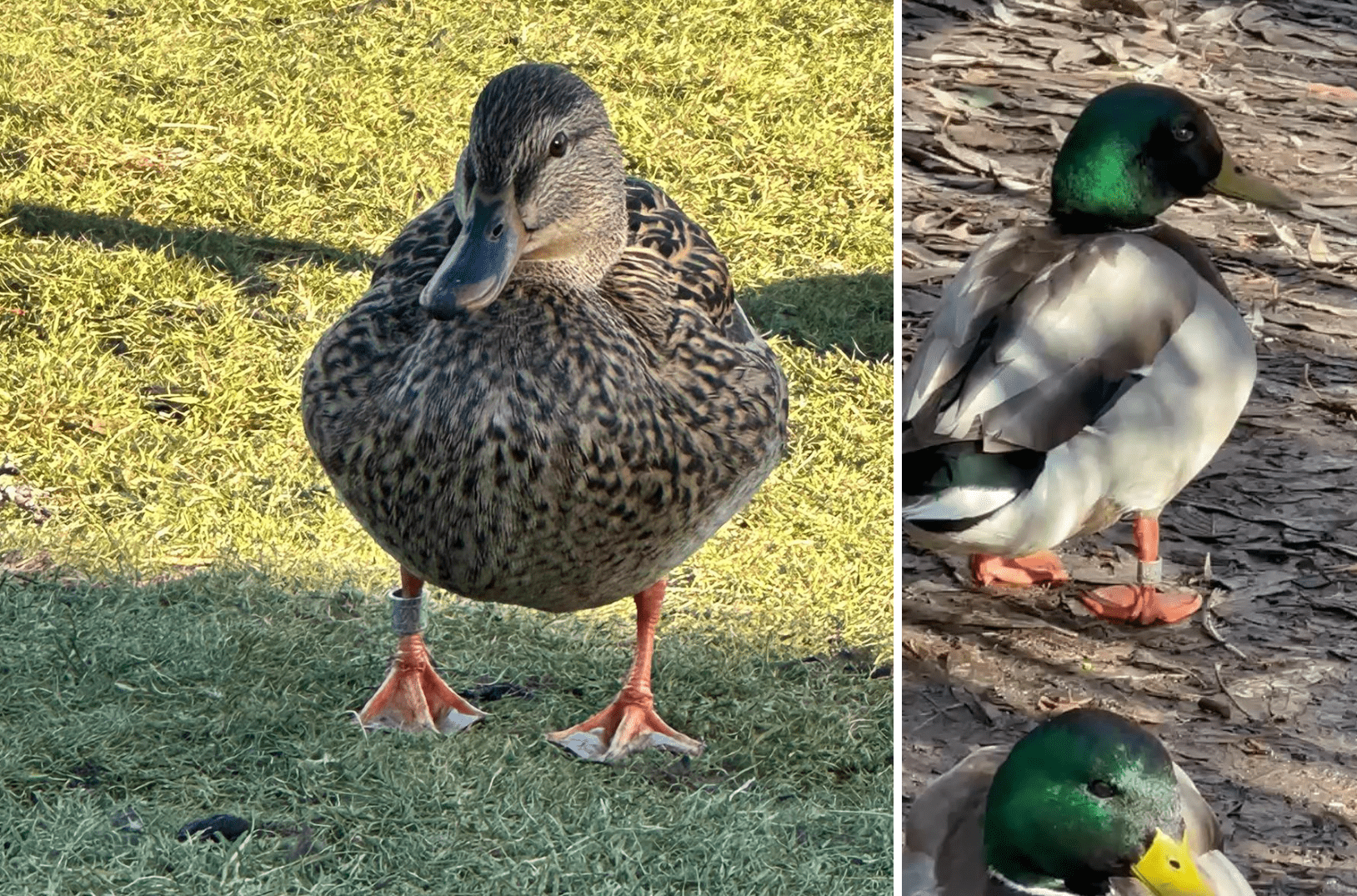

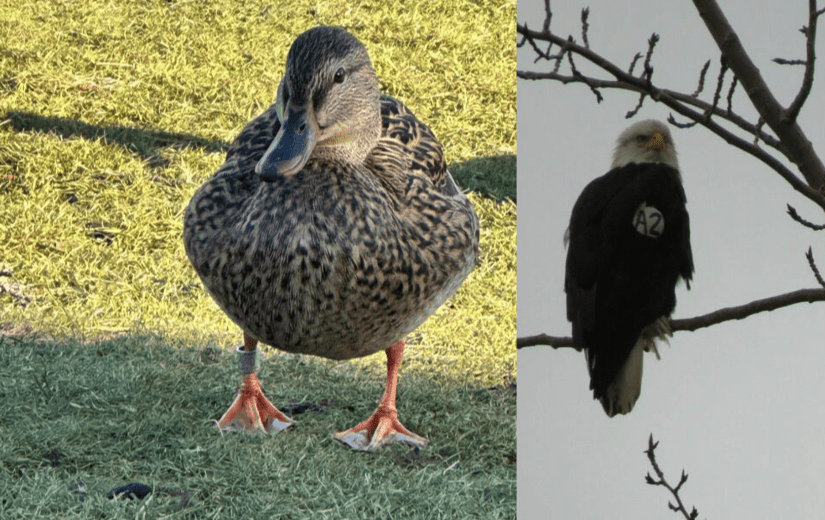

If you spot a bird with a metal band or coloured markers, it’s no accident. The North American Bird Banding Program is jointly administered by the Canadian Wildlife Service and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). More than 1.2 million birds are banded in Canada and the U.S. each year! When banded birds are seen days, weeks, months or even years later, this data helps wildlife scientists monitor and conserve migratory bird populations by providing information on the distribution and movement of species.

Your contribution is important – the program relies on the public to report bands and other markers they see. You can help by reporting birds online at reportband.gov or call toll-free 1-800-327-BAND (2263) to leave a message.

Taking a photo can help you to read the band numbers, but don’t try to chase or catch wild birds just to read a band. It may take a few sightings to get the complete band number.

After your information has been submitted, a certificate of appreciation including the bird’s banding information will be emailed to you. The program will also let the bird bander know when and where the bird was seen.

Some birds released from Wild ARC are banded as part of this federal program, which means we occasionally get updates on sightings of former patients. While out for a walk, a Wild ARC staff member noticed two mallards sporting silver leg bands. With lots of photos from various angles and a bit of detective work, the pair were confirmed to be former patients who had come to Wild ARC as orphans in the spring of 2022.

We are always thrilled to see these former patients thriving in the wild with their own kind.

Pigeons are not banded as part of the North American Bird Banding Program. If you find a banded pigeon, they are likely a domestic pigeon that has become lost or tired. Generally, pigeon bands have letters representing a racing association who can help to get in touch with the owner:

Learn more about the North American Bird Banding Program:

NOTE: The BC SPCA’s Wild ARC is NOT currently able to accept fur coat donations.

The sad facts about fur are hard to ignore, and many people are looking to make their home more fur-free. Sometimes this is as small as fur trim on a sweater, hat, or other accessory, or sometimes it’s an entire coat inherited from a family member. If you want to re-purpose or re-home old furs, consider these options:

Remove fur trim

Simply removing the fur is the easiest way to reclaim your clothes. Enlist the help of a local tailor for more complicated projects that might require expert removal and repair. Ask to keep any fur trimmings so you can ensure they stay out of the fashion industry.

Donate fur

The BC SPCA is frequently contacted from people wishing to donate their fur coats to Wild ARC and other wildlife rehabilitation centres. This has been so successful over the last few years that many now have an overabundance of furs! Unfortunately, furs can’t be cleaned the same way as other textiles – for the safety of our patients, they have to be discarded once soiled. Please note Wild ARC is NOT currently able to accept fur donations.

Research and consider donating to local animal protection groups or museums, who sometimes have educational uses for fur.

Communities living in the Arctic may also have a need for fur donations. Fur is considered a necessity in this part of Canada, where temperatures can drop below zero for nine months of the year and can get as cold as -65C with the windchill. Fur and leather are also very expensive in the Arctic, so donating fur coats is a positive way to support northern communities.

Fur burial

For some people, simply laying the fur to rest is one way to find peace. Find somewhere acceptable to hold a small ceremony and bury the fur, first removing any synthetic components.

Lead poisoning is a serious condition that affects wild birds and other animals when they are exposed to lead – from surviving a lead shot, ingesting spent ammunition or fishing tackle, or secondary poisoning from eating carcasses contaminated with lead. Lead is a toxic metal and even a small amount is enough to kill an animal.

Some affected animals don’t show symptoms, while others are lethargic or have trouble breathing, suffer from blindness, or experience muscle paralysis, seizures and eventually death. Lead poisoning isn’t always obvious because poisoned animals are more likely to be killed in vehicle collisions, window strikes or entanglement in fishing gear, or will seek shelter and isolation to suffer in silence and are never found.

Lead shot is prohibited in Canada, and lead sinkers and jigs are prohibited in Canada’s national parks and wildlife areas. Unfortunately, these items are still used and the remnants of them are still present in our ecosystems. The impacts of lead poisoning are preventable – the BC SPCA recommends only lead-free alternatives to keep this toxic metal out of the environment.

Just because you see a rabbit in the wild doesn’t mean they’re a “wild” rabbit. Free-living populations of domestic rabbits exist in urban areas — these rabbits are often abandoned pets or their offspring. The BC SPCA is opposed to the abandonment of pet rabbits and it is also illegal under the BC Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act.

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD) has been found in feral rabbits on Vancouver Island and in the Lower Mainland – learn more about RHD.

How can I tell them apart?

Eastern cottontails are a wild species, with brown bodies and short, fluffy white tails. Cottontail rabbits are small (~1 kg) animals, with small ears and lean legs and bodies.

Domestic feral rabbits can be a variety of colours like black, tan, grey, white or spotted, and can look like Eastern cottontails at first glance – like this rabbit found living outdoors:

Feral rabbits are generally larger (1 – 2.5 kg), with big wide floppy ears and a more boxy face. Can you spot these differences in the photos above?

Both types of rabbits are attracted to sheltered, landscaped yards with dense shrub or undergrowth. Eastern cottontails don’t dig burrows, instead nesting in shallow depressions in grassy areas. Feral rabbits do burrow, and have a reputation for damaging lawns and gardens. For help addressing problems with feral rabbits, read our best practice sheet on rabbits.

Wild rabbits are normally solitary animals, usually seen on their own. Feral rabbits are social animals and may be seen in small groups.

Don’t judge a rabbit by their behaviour – domestic feral rabbits that aren’t used to people can be very fearful, and wild rabbits may be approachable if they’re sick or injured. In general, rabbits living in the wild are highly susceptible to stress – trying to capture or restrain them may cause death, a condition known as capture myopathy.

I found a baby rabbit

Baby rabbits found alone don’t always need help – it’s normal for a mother rabbit to leave her babies hidden in the nest for long periods of time. The mothers will come back only a few times a day to feed the babies, who wait quietly while hiding from predators.

If you’re unsure if they need help, or the babies (and any adults) are obviously injured (e.g., bleeding, broken limbs), check our webpage for more information or call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline for advice at 1-855-622-7722.

What do wildfires mean for wildlife? Just like people, wildfires also impact wildlife. Wild animals have developed strategies to fly, run or bury themselves to escape from fires, but the change in habitat and food resources will have a lasting impact for generations. Especially for fires that occur near urban and suburban areas, you may see wild animals passing through or resting in your yard as they search for safety.

During wildfire season, or in times of severe drought, you can help wild animals:

- Prevent forest fires – learn more about how you can prevent forest fires.

- Don’t feed the animals – feeding wildlife does more harm than good, and can create dependence on humans. Wild animals can find food on their own, even in severe conditions.

- Let them rest – if wild animals are fleeing a fire, they will already be scared and tired. Don’t scare them, and be patient as they rest before moving along.

- Keep your pets on-leash or inside – this helps keep pets and wildlife safe by preventing conflicts.

- Report injured wildlife – if you find an injured animal or suspect they need help, contact your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice.

If you do find a wild animal in trouble as a result of a fire, they need help as soon as possible. Before trying to rescue them, make sure they need your help. Trying to catch a wild animal that’s just resting will scare them, wasting precious energy that may be needed to escape a spreading fire.

A wild animal might need help if:

- There are obvious signs of injury (burns, blood, wounds, etc.)

- They have been hit by a car, hit a window, or been caught by a pet

- They seem ‘sleepy’ or don’t respond when you approach

- They seem dizzy or disoriented, or stumble and fall when they move

- They are a baby and have been crying for a long time, are covered in bugs, or are cold and not moving very much

If you’re not sure whether a wild animal needs help, call your nearest wildlife rehabilitation centre, or the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722, for advice.

Learn more about how you can help pets and other animals during wildfire evacuations.

Research suggests that lobsters (along with other decapod crustaceans such as crabs) have the capacity to feel pain. While some believe the science is inconclusive, others consider the evidence as strong as the evidence for pain in fish.

The BC SPCA believes that it is best to err on the side of caution by avoiding potentially painful practices such as boiling these animals alive. Instead, we recommend that lobsters be humanely killed by trained and competent personnel before purchase. Humanely killing a lobster is typically a two-step process: the animal is first rendered insensible (incapable of feeling pain) before being killed.

As an animal welfare organization, the BC SPCA acknowledges that recreational fishing for food and for sport is an important activity to many Canadians.

We believe that recreational fishing — like hunting — should be carried out in an ethical, humane, responsible and sustainable manner by qualified and experienced anglers, who abide by applicable laws and regulations. The best possible angling practices and handling methods that minimize stress should be employed, together with the use of gear that causes the least amount of injury and pain.

When fish are caught to be eaten, they should be killed humanely. The handling methods and equipment used should ensure that fear and pain are kept to absolutely minimal levels prior to and during killing.

When catching and releasing fish, anglers should take into account how much the fish is likely to suffer, and how likely the fish is to survive. Ultimately, catch-and-harvest may be preferable to catch-and-release, given how poorly fish can fare after they are released. Studies have shown that, depending on the species and method of capture, post-release mortality can range from 0 to 95 per cent.

Though some are still skeptical, evidence that fish can feel pain has been growing for decades. It has now reached a point where the sentience of fish (their ability to perceive, experience and feel) is acknowledged by leading scientists and organizations around the world. For instance:

“…there is as much evidence that fish feel pain and suffer as there is for birds and mammals…”

– Dr. Victoria Braithwaite, author of Do Fish Feel Pain?

“The evidence of pain and fear system function in fish is so similar to that in humans and other mammals that it is logical to conclude that fish feel fear and pain. Fish are sentient beings.”

– Dr. Donald Broom, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge

“…it would be impossible for fish to survive as the cognitively and behaviourally complex animals they are without a capacity to feel pain.”

– Dr. Culum Brown, editor of The Journal of Fish Biology

“…the preponderance of accumulated evidence supports the position that finfish should be accorded the same considerations as terrestrial vertebrates in regard to relief from pain.”

– American Veterinary Medical Association

Like other animals, fish respond to painful events with changes in their behaviour and physiology. While the parts of their brain involved in the pain response are not anatomically the same as in mammals, for example, their function is very similar. Pain teaches fish to avoid things that cause them harm, helping them to respond effectively to their environment and, ultimately, to survive.

Seeing a bear from a safe distance can be a thrilling experience, but what do you do in a surprise encounter with a bear?

Bears are omnivores that eat mostly berries and fish. Their habitats often overlap with ours in places like parks, resorts, hiking trails, or simply our backyards. Bear attacks are very rare – most of the time, they are happy to go unseen by people and will move along on their own. They can lose their healthy fear of people if we’re not careful with our food and garbage, or they may feel threatened if people come too close to their babies.

If you encounter a bear in the wild or in the city, remember to:

- Stay calm and back away slowly – do not run, climb a tree or make any sudden movements or loud noises, back away and give the bear plenty of space so they can move on

- Never feed a bear – bears used to being fed by humans can lose their fear of people and lead to unwanted conflicts and aggression

- Make yourself look big – stand tall or stay together in a group, do not kneel down

- Keep children and pets close – pick up small children and pets so you know where they are while watching the bear

- Don’t make eye contact with the bear – they may see this as a threat or a challenge

- Move indoors – if possible, move indoors and bring children and pets with you

- Report aggressive or threatening encounters by calling the Conservation Officer Service at 1-877-952-7277

Mother bears are protective of their young, so do not approach a baby bear, as mom will be watching from close by. Never try to out-run a bear or climb trees to escape.

Read more about living with bears in B.C.

Black bears vs. grizzly bears

B.C. is home to two kinds of bears – black bears and grizzly bears. Despite their name, black bears can be black, brown, silver, cinnamon or even white (called “Kermode” or “spirit” bears). They are adept tree climbers with large ears, short claws, a long nose, and don’t have a shoulder hump like grizzly bears. Black bears are the most common type of bear near B.C.’s largest cities.

Grizzly bears are sometimes called brown bears, but they can also be black, brown, or blond. They have relatively small ears, long claws, a dish-shaped face, and have a distinct shoulder hump. Grizzly bears generally live in rural and remote areas of B.C. and thrive in undisturbed habitats.

Cougars are found throughout much of B.C. and are also known as mountain lions or pumas. Cougars are generally very secretive and rarely seen. However, cougars may occasionally pass through urban settings, or when young cougars leave their parents, they start looking for their own sources of food and places to live. Sometimes they end up in urban areas, parks or hiking trails.

Prevent problems with cougars

If you know cougars are active in your area, follow these tips to keep pets safe:

- Before letting dogs into your yard, turn on the lights and make some noise – check to make sure there aren’t any unexpected animals in your yard

- Keep dogs on leash and stick to well-lit areas when walking dogs at night – avoid dark, forested wildlife areas after sunset

- Keep cats indoors, or in secure outdoor enclosures – at minimum, make sure cats come in at night

What to do if you see a cougar

Although they are skilled predators, cougar attacks are rare. However, if you see a cougar in the wild or in the city, stay calm and follow these steps:

- Make yourself look big – stand tall, raise your arms and spread your legs

- Maintain eye contact and don’t turn your head – stay focused on the cougar

- Make loud noises – yell, clap your hands, use a bear bell, or bang things together

- Don’t leave until the cougar leaves – be sure the cougar has moved on before you leave

If you have small children or a dog, pick them up or keep them close in front of you. This may feel counter intuitive, but this way you can maintain control and face the cougar. A child or dog behind you may try to run away or divert your attention from the cougar. Act like you are bigger and stronger than the cougar so they will see you as a threat.

Photo credit: Gary Schroyen

Photo credit: Gary Schroyen

The BC SPCA generally doesn’t recommend feeding wildlife – but what about bird feeders? Although common worldwide, bird feeding does carry risks.

In the absence of disease outbreaks, feed birds only in harsh winter conditions, and follow these tips:

- Prevent disease – clean up spills and clean feeders regularly using a 9:1 (10%) bleach solution. Take feeders down during disease outbreaks, like salmonella or avian influenza.

- Avoid window strikes – set up feeders very close to windows (within 1 m) to minimize collisions. Use window protection products to prevent birds from colliding with windows.

- Keep cats inside – collar bells will not stop cats from killing birds.

- Don’t feed other animals – bird seed can attract animals like mice, rats, squirrels, raccoons, deer or bears. Clean up spilled seed and make your bird feeder inaccessible to other animals.

In the warmer months, there are usually abundant natural food sources available for birds. You can also attract birds to your yard naturally with native plants and well-managed bird baths and bird houses.

Feeding hummingbirds has special considerations – read more about hummingbird feeders and how to make hummingbird nectar.

Read our position statement on wildlife feeding.

Nectar feeders provide a food source for hummingbirds in winter, but they must be cleaned regularly and kept fresh and full. It’s important to take this commitment seriously!

Feeders often attract unusually large numbers of hummingbirds to one area – this can be a joy to watch, but also means any fungus or bacteria in the feeder will affect many birds. These infections can cause their tongues to swell and often result in death, a sad outcome for birds and bird lovers. Feeders that are left empty or left to freeze can also lead to starvation for the birds that have come to rely on them.

If you commit to winter feeding, you must commit fully. Non-migratory hummingbirds may come to rely on this food source and will suffer if it is interrupted. Don’t put hummingbird feeders out if you’re not prepared to clean and maintain them.

If you’re not ready for this serious commitment, bring you nectar feeders in starting in September, before their fall migration. Hummingbirds are smart and adaptable, and this will give them time to find another food source before winter hits.

Clean feeders with a solution of one part white vinegar to four parts water about once a week. Change the nectar solution every few days, ensure it never freezes, and can be provided through the whole winter. Have a friend or neighbour check your feeder if you’re away. In harsh temperatures, you may need to bring your feeder in at night to prevent freezing – this won’t disrupt the hummingbirds if the feeder is put back out first thing in the morning. You might want to keep two feeders handy so you can alternate between them.

To make nectar:

- boil water for two minutes

- mix one part white sugar to four parts water

- allow mixture to cool before filling feeder

- never use honey, sweeteners, molasses, brown or raw sugar

- don’t add red food colouring or other products

While there are many different recipes available online, this is the only one we can recommend, and use at our own Wild Animal Rehabilitation Centre. White sugar is closest to the sugars they find in nature, other types of sugars or recipes could make them sick and die.

Even in winter, do not change the ratio of sugar to water. Adding more sugar may help prevent freezing, but it’s not healthy for these sensitive little birds.

Read more about feeding birds and other wildlife (PDF).

It is pretty common for a dog to get skunked – they’re curious creatures and that can lead to a spritz or a full-on soaking of an intense, foul-smelling spray from the skunk.

How to remove skunk smell:

- 1 litre of 3 per cent hydrogen peroxide

- ¼ cup baking soda

- 1 tsp liquid dish soap, such as Dawn

Combine ingredients and shampoo your pet. Rinse with water and repeat if necessary.

Skunk spray is often centred around the facial area. Avoid your pet’s eyes when using the solution on the face. If any product does get into your pet’s eyes, it’s important to rinse the area very well.

In future, be proactive

Skunks are nocturnal animals with poor eyesight and limited climbing skills. They only use their spray as a last resort when startled, cornered, or attacked. If you see a skunk, back away slowly and quietly to avoid a spray. Keep your dog on a leash when you’re out walking in low light.

Learn more about coexisting with skunks.

Any company can call themselves “humane” – but like many food-labelling claims, it doesn’t mean they are using animal-friendly methods. To help make your choice easy, the BC SPCA developed AnimalKind.

Any company can call themselves “humane” – but like many food-labelling claims, it doesn’t mean they are using animal-friendly methods. To help make your choice easy, the BC SPCA developed AnimalKind.

AnimalKind is the first-ever animal welfare accreditation for pest control companies. AnimalKind companies meet the BC SPCA’s science-based standards (PDF) and have to pass an audit before they are accredited.

Call an AnimalKind company to help you with rodents and other wildlife in your home.

If AnimalKind companies are not yet available in your area, make sure to ask the following questions before hiring a company:

- “Do you trap and relocate wildlife?” A good wildlife control company prioritizes prevention and exclusion and only releases wildlife in their home range when exclusion techniques are not possible. In baby season, good companies will ensure all young are reunited with mom. Animals that are live trapped and removed from an interior space will be released within their home range.

- “Do you use non-lethal techniques?” A good wildlife control company will control most wildlife non-lethally. However rodents such as mice and rats can cause significant health and safety issues and may need to be killed if prevention and exclusion techniques are limited, have been ineffective, or if the rodent population is a health and safety concern.

- “If you kill rodents, what techniques do you use?” Never hire a company that uses glue traps or multi-catch traps that do not open. Glue traps cause significant suffering and often catch non-target animals. Multi-catch traps like the “ketch-all” do not open and there is no way to humanely kill the animals caught inside.

- “What’s in the box?” Bait stations can hold snap traps, glue traps, or poisons or simply trap rodents inside without food or water, resulting in a slow death. Know what’s inside.

Thanks to the incredible advocacy of passionate wildlife lovers, on July 21, 2021, the province banned the sale and use of rodenticides containing the active ingredients brodifacoum, bromadiolone, or difethialone (known as second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides or SGARs). Exemptions are currently allowed for designated essential services and agricultural operators.

What is humane pest control?

When wild animals get into our yards and our homes, we sometimes call them “pests”. Rodents are the most common cause for pest control in our houses, but sometimes animals like raccoons, deer, rabbits and pigeons get into trouble too. Even “pests” deserve to be treated humanely.

The best solution is to prevent the problem before it starts. Make sure you’re not accidentally giving them food (like pet food, bird seed, fruit trees, fish ponds) or shelter. Make sure your garbage and compost is in wildlife-proof containers. Seal gaps or holes in sheds, crawl spaces, attics and porches before they become a comfy nest or den.

Wildlife removal

Trapping and relocating wildlife is not a permanent or humane solution. Trapping in the wrong season can also orphan babies. If you have to remove an animal, call an AnimalKind company that gently removes them instead of trapping/relocating or killing.

If there are no AnimalKind companies in your area, use the questions above to find a humane pest control company.

Learn more about urban wildlife.

Glueboards, poisons and snap traps

Glueboards or glue traps are plastic or metal trays coated with glue designed to catch rodents. These traps are legal and can be found in stores, but they cause rodents and other animals to suffer tremendously. Birds, small wildlife and even pets can get caught in this sticky situation. Never use glueboards!

Rodent poisons or “rodenticides” are used widely, but they cause a slow and painful death. Rodenticides are also dangerous for owls, eagles and even cats that eat poisoned rodents.

Snap traps cause a quick death for mice and rats, but can be dangerous to wildlife and pets unless they are kept in a locked box or wall interior. Call an AnimalKind company if you need help with mice and rats in your home.

What is “humane”?

Any company can call themselves “humane” – but like many food-labelling claims, it doesn’t necessarily mean they are using animal-friendly methods.

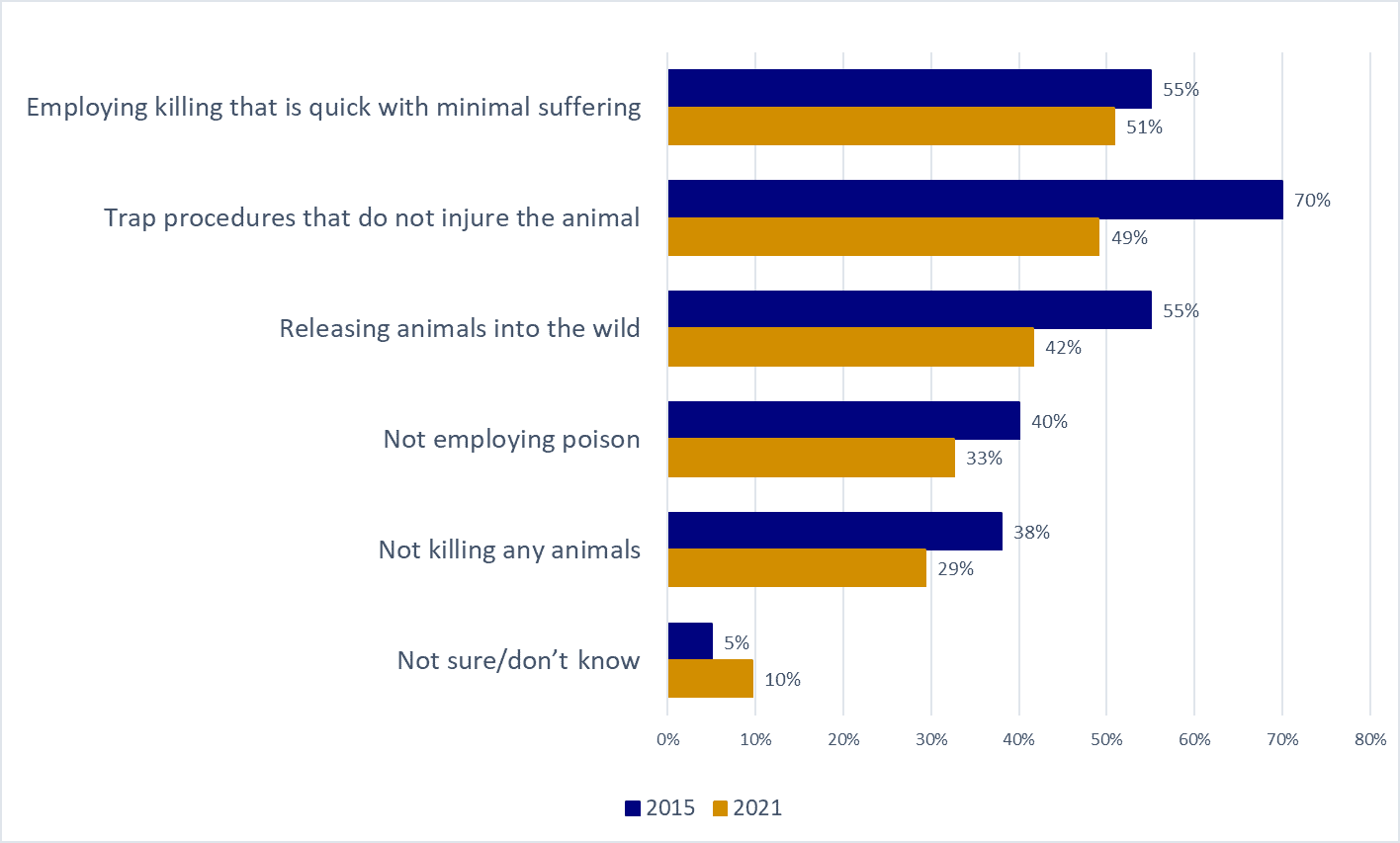

In May 2021, thanks to a grant from the Vancouver Foundation, we conducted a poll* of 860 BC residents and learned “humane pest control” is still misunderstood. The term “humane” used in pest control still varies in definitions among BC residents surveyed since our last 2015 poll**.

When asked, what do you think the term ‘humane’ means in terms of pest control? Respondents could choose more than one response and they said ‘humane’ is:

**Vision Critical poll conducted for the BC SPCA September 2015 (n=803, margin of error ±3.4%, 19 times out of 20)

Subscribe to AnimalKind to receive news and updates!

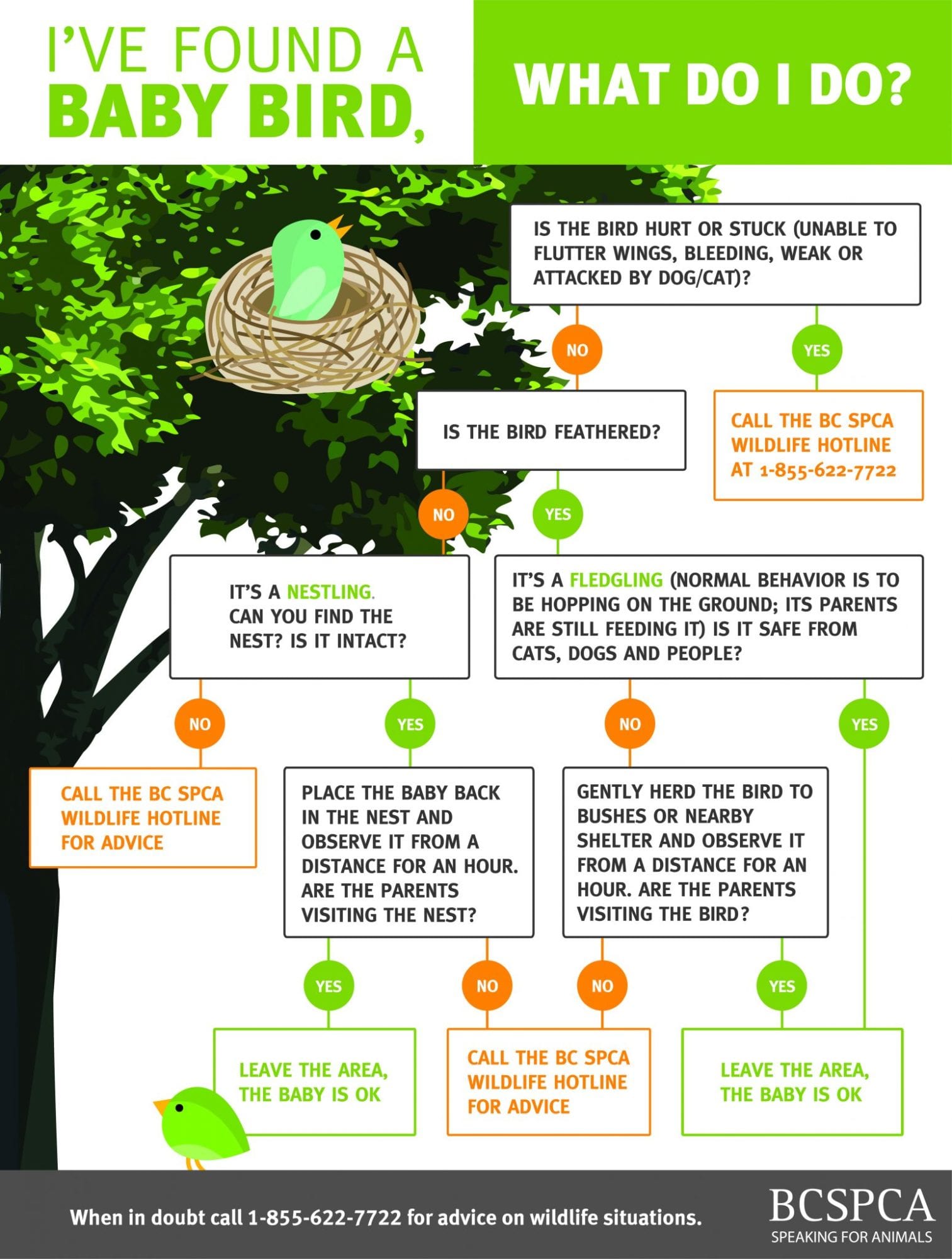

A baby bird may be blown out of a nest by wind or rain, or even dropped after a failed predatory attack. If the bird isn’t hurt, you can place it back in the nest. Unlike mammals, birds have a poor sense of smell and will not reject babies touched by people.

Watch the nest for one to two hours to confirm the parents are coming back to feed the baby. If the parents don’t return, or the baby bird is hurt, contact your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice. Sometimes parents will reject baby birds if there is something wrong with them, or they are too weak.

In the spring and summer, you may see healthy-looking birds on the ground that can’t fly. These young birds are called fledglings. Birds at this age are just learning how to fly.

The parent birds are usually close by for protection, but will not feed the fledglings as often. This makes the young birds hungry so they hop out of the nest to explore.

Try to keep the area safe while these birds learn how to fly. Keep cats and dogs inside or on leash, and leave the area undisturbed.

If the birds are in an unsafe area, like a road or parking lot, call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline for advice at 1-855-622-7722. Read our care sheet found a baby bird (PDF) and find out more about what to do if you find a baby bird.

Read more about rescuing wild animals.

Gulls

Gulls often nest on the flat roofs of commercial or apartment buildings. Most times, the young gulls will fly off with their parents when they are ready. As the young gulls are learning to fly, sometimes they jump or tumble from the roof before they are able to fly well. When this happens, they often land in an unsafe location and are unable to fly to safety.

If a young gull is stuck in an area without food for more than a day, and you do not see adult gulls coming down to bring food to the baby, it might need to be rescued. In this case, contact your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline for advice at 1-855-622-7722.

Read more about rescuing wild animals.

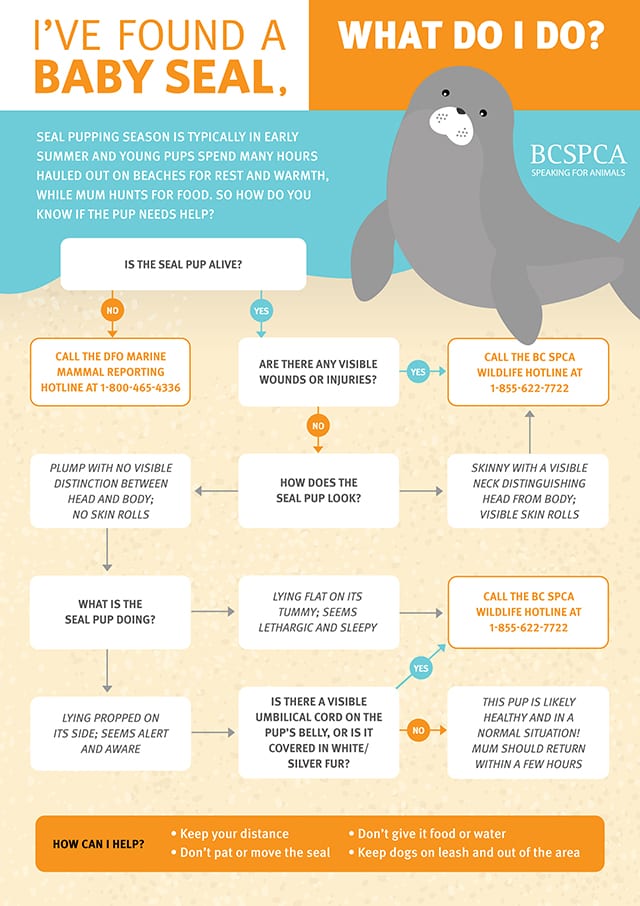

A mother seal will leave her pup on a beach or rocks near the water while she hunts for food. A seal pup alone is not always an orphan. Healthy seal pups look plump with no skin rolls, and seem alert and aware.

Keep dogs on leash and away from the seal pup. Also, discourage people from approaching – although baby seals are very cute, this is very stressful for them as we appear as predators.

If the seal pup is injured, looks skinny or lethargic and sleepy, contact Marine Mammal Rescue Centre (MMR) at 1-604-258-7325 or call our Animal Helpline for advice at 1-855-622-7722.

Find out more about what to do if you see a baby seal or download our brochure “What to do if you find a baby seal” (PDF). Read more about rescuing wild animals.

If you have found a baby wild animal, contact your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or call our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice. They can advise you on how to return the baby safely, or how to tell when they need help.

You can also read more about what to do if you have…

Whether it’s a baby bird, squirrel, deer, seal, raccoon or skunk, a baby animal’s best chance for survival is with its mother. Finding a baby animal doesn’t always mean they’re in trouble – many times, you won’t need to do anything at all. However, if the baby is hurt or sick, or you know the mother is dead, they will need help right away.

Can I touch a baby animal?

Birds have a poor sense of smell, and will not reject babies touched by people. This means you may be able to place baby birds back in their nest. Mammals have a much more keen sense of smell, however, they are also very dedicated parents. A reunion may still be possible – under the guidance of a wildlife rehabilitator – even when babies have been handled by people.

Before handling any animals, call your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice on how to reunite baby animals with their mothers.

Should I feed a baby animal?

Never attempt to feed a baby animal, this usually does more harm than good. Wild animals require professional care, and it is illegal for you to keep and care for a wild animal.

Read more about rescuing wild animals.

Want to receive more stories like this, right in your inbox? Subscribe to WildSense, our bi-monthly wildlife newsletter.

If you find a bird that has struck a window, take note of any obvious signs of injury. Place the bird in a cardboard box with air holes and a secure lid. Make sure the box is just large enough for the bird to extend their wings (not too big, not too small).

Put the closed box in a safe, quiet and dark place. Contact your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice. Do not give the bird food or water.

Even if they become more active, do not let the bird go once you have contained them. Birds often have internal injuries after hitting a window, and will need help.

Learn more about how to prevent bird-window collisions, and buy decals and tape for your windows to help birds.

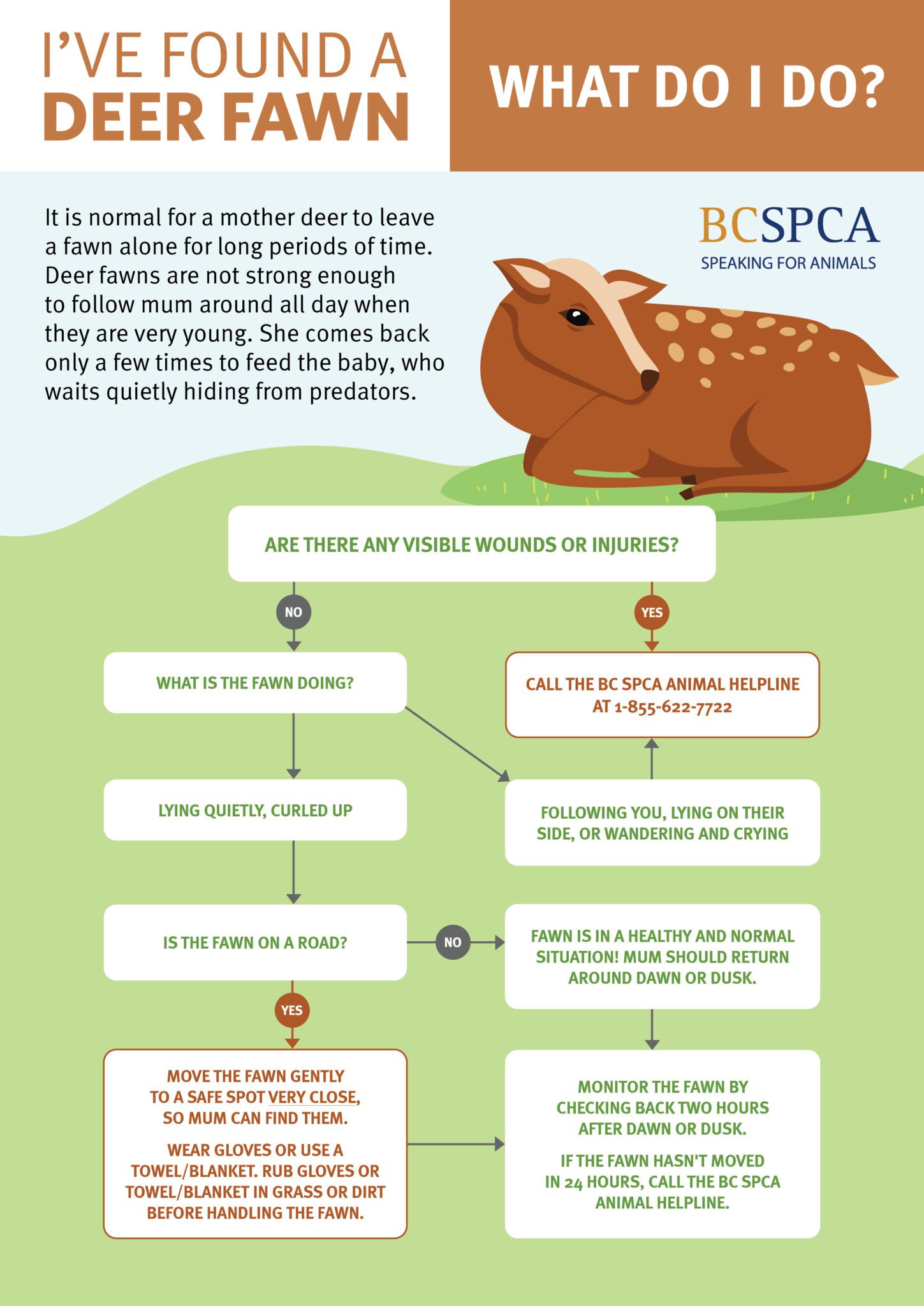

If you have found an injured deer fawn or believe a fawn may be orphaned, call our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 or the Conservation Officer Service at 1-877-952-7277 (RAPP). They will help you assess the animal and find a wildlife rehabilitator.

Unfortunately, wildlife rehabilitators can’t often help injured adult deer, as they are too high-stress to keep in a captive setting. Even when injured, they can be very dangerous because of their size and strength. If you can approach an injured adult deer and they don’t run away, they are likely too badly injured to survive.

Call your local RCMP or Conservation Officer Service to humanely euthanize an injured adult deer.

Read more about rescuing wild animals.

Every year, wildlife rehabilitators care for healthy fawns that were thought to be orphaned. It is normal for a mother deer to leave a fawn alone for periods of time. They come back only a few times a day to feed the baby, who waits quietly while hiding from predators.

If you find a fawn lying quietly, and you are worried they have been abandoned, don’t disturb them. Check on the fawn from a distance for the next 24 hours – the mother will likely return and move the baby to a new spot.

If the fawn has not moved after 24 hours, starts to cry, is wandering aimlessly, or looks injured, contact a wildlife rehabilitator right away.

If the fawn is in an unsafe location, move them gently to a safe spot very close by so they won’t get hurt.

Print our card on what to do if you find a deer fawn (PDF).

Read more about rescuing wild animals.

Yes, some school programs will give you credit for volunteering with the BC SPCA.

Practicums at Wild ARC are available for university and professional training credits.

Practicums at the Vancouver Branch are also available to university students if registered through the University of British Columbia.

High-school work experience may also be available at your local BC SPCA branch. Contact them directly for details.

Veterinary and registered animal health technologist externships may also be available at certain BC SPCA Hospitals and Clinics. Contact them directly for details.

Cats have bacteria in their mouths that can kill a bird if it is not treated with specialized antibiotics. Even if the bird doesn’t look injured, a small scratch or puncture can kill them. Do not try to treat the bird yourself. Gently contain the bird in a well-ventilated box and bring them to your nearest wildlife rehabilitation centre in British Columbia.

Still need help? Read more about rescuing wild animals or call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice.

Read more about preventing problems between cats and birds, or about pets and wildlife (PDF).

Don’t try to take care of injured or orphaned wildlife yourself – it is illegal and can cause harm. Contact your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 (1-855-6BC-SPCA) for advice on wildlife situations.

Except for Wild ARC, BC SPCA branches do not rehabilitate wildlife. A local veterinarian may be able to help euthanize a suffering animal, but they do not have the permits or facilities to provide full rehabilitation services. Call your local RCMP or Conservation Officer Service if you see adult deer/elk/moose/bears injured on roads.

Read more about how to rescue wild animals.

The BC SPCA can’t stop a legally-permitted cull from happening in your community. However, the BC SPCA can intervene if the killing methods are inhumane (by law) or if animals are in distress. If you witness an animal in distress during a cull, call our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722. Document evidence by taking videos or photos, but do not trespass on private property or put yourself in danger.

The BC SPCA is opposed to culling animals when there is no evidence to support it, or it can’t be done humanely. The BC SPCA’s primary approach to wildlife conflicts is coexistence, and changing human behaviour to prevent problems. International and BC SPCA experts agree there are many steps that must first be taken to justify ethical wildlife control.

Deer culls

The BC SPCA recommends using non-lethal strategies to solve human-deer conflict. Communities should aim to prevent conflict by educating residents about coexisting with urban deer. Culling is an inefficient, short-term solution and should not be a default practice.

Read our position statement on urban deer.

Download our urban deer pamphlet (PDF).

Geese and other bird culls

The BC SPCA recommends hazing and environmental modifications to prevent conflicts with birds, as well as providing education that discourages feeding by the public. When appropriate, fertility control is a non-lethal way to limit reproduction, though permits are generally required.

Read our best practice sheets for:

Wolf culls

Wolf culls in B.C. and Alberta have drawn significant criticism. Experts criticize the inhumane methods and lack of evidence that killing wolves will save caribou or other species. Culling can break up wolf pack structures and create an imbalance with other species in the area. Even with skilled shooters, shooting wolves from helicopters can cause stress and death may not be quick and painless.

Read our position statement on predator control.

Coyote sightings in the city are normal, even during the day. You can help prevent conflicts by respecting their space and being a responsible pet guardian. Feeding coyotes causes them to lose their healthy fear of people – keep your garbage secure and don’t leave food outdoors.

If you see a coyote, scare them away by yelling, stamping your feet and waving your arms. Make lots of noise and try to look big. This may feel silly, but will help the coyote avoid problems in the future.

If pets can’t be kept indoors, make sure they come in at night to keep them safe.

Report a coyote sighting in Metro Vancouver or read more about coexisting with coyotes. Call the Conservation Officer Service at 1-800-663-9453 to report an aggressive or threatening coyote.

Crows and ravens can be hard to tell apart, especially from far away. Crows are smaller than ravens – they have a wingspan of about 92 cm, compared to a raven’s 117 cm.

Crows

Smaller, straight beak

Fan-shaped tail

Characteristic “caw”

~92 cm wingspan

Ravens

Large, thick, rounded beak

Diamond-shaped tail

Deeper “croak”

~117 cm wingspan

Baby ducks and geese can usually make their own way down from a nest on a roof. But, they may need your help if:

- The building is more than six meters (two storeys) in height

- There is a barrier higher than 13 cm preventing them from hopping down

- The ground below is concrete, cement or other hard material

In any of the above cases, call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 to help you develop a rescue plan.

Ducks sit on their nest for three to four weeks before the babies hatch. To prevent the babies from hopping into the pool, cover the pool a few days before you expect the babies will hatch. The babies are small and don’t have waterproof feathers, so they can get hypothermia or drown if left in the water.

If a baby duck or goose ends up in your pool:

- Toss floating objects, like flutterboards, in the pool immediately to give babies temporary resting places

- Make a ramp using foam pool floats, patio chair cushions, or a wooden plank. You can use an empty pop bottle tied to the underside to help it float

- Use a pool skimmer to herd babies towards ramps, but don’t chase them. Chasing causes more stress and will exhaust the babies

- Open the gates to the pool area so the family can move out and find a better water source

If you need further advice on a nesting duck or goose family, call our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722.

After ducklings and goslings hatch, their parents walk the babies (who can’t fly yet) to nearby water sources. Sometimes the families get stuck at road medians if they try to cross a highway or busy street. This creates a tricky situation where both the animals and the rescuers might be in danger. Trying to herd the family can cause them to panic and run into traffic, and rescuers may disrupt traffic or risk their own safety.

The best way to help duck or geese families trying to cross the street is to contact local police for help stopping traffic. Once traffic is stopped, slowly and calmly herd the babies and parents to safety. Only try to capture the family if necessary for their safety. If the parents (or babies) panic and scatter, the rescue and reunion can become complicated.

Call our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for help with wildlife issues, including advice on how best to help duck or goose families.

Ever wonder how to tell ducklings and goslings apart? At first glance they look similar, but they have distinct differences in colour and size. Mallard ducklings are much smaller than Canada Goose goslings. Mallard ducklings have dark chocolate brown and yellow markings with a dark line through their eye. Goslings are an olive-green and yellow colour, and do not have the dark line through their eye.

If you find a duckling or gosling wandering alone, with no adults or other babies nearby, they need help. Contact your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722.

Classrooms are an unnatural and stressful setting for wild or exotic animals. Seeing these animals outside of their natural wild habitat does not provide educational benefits and will likely lead to their early death.

Also, wild and exotic animals can carry diseases that may be passed onto children, who are still developing their immune systems.

There are many ways to experience and appreciate wild and exotic animals in nature, online or through documentaries. Compassion starts young, so let’s keep animals in nature.

Read our positions on animals in schools, educational visits using animals, exotic pets and wildlife welfare.

Wild animals are indigenous to Canada, but exotic animals are wild animals from other countries. These animals can be captured from the wild or bred in captivity. Exotic animals are often sold in the international pet trade.

The BC SPCA does not support keeping wild or exotic animals as pets, due to their unique physical and emotional needs. These animals often suffer in care because of their specialized needs.

Under provincial law, it is illegal to keep certain wildlife and certain dangerous exotic animals like tigers, primates or crocodiles, as they are designated as Controlled Alien Species.

Many cities also have exotic animal bylaws that make it illegal to keep some or all exotic pets. Check with your local municipality for a list of banned exotic animals.

Read more about exotic pets.

It is illegal to keep or sell a wolf as a pet in B.C. Some dogs are sold as “wolf-dog hybrids” for thousands of dollars, but they are really just dogs and have little to no wild wolf in them. Genetic testing is available to confirm hybrid status, however the animals’ behaviour is often used to assess their “wildness.”

The BC SPCA is opposed to keeping, breeding and importing wolf-dog hybrids as pets. Cross-breeding a wolf and dog counteracts 12,000 years of domestication. These animals are difficult to train and contain, develop stereotypies in captivity, and often show aggression toward other animals and humans. They need a high level of care that is difficult to achieve and do not make good pets.

Wolf-dogs already in captivity should be sent to accredited sanctuaries and never used for public attractions as roadside zoos or “walks with wolves”.

Photo by John E. Marriott

It is illegal to keep wild foxes as pets in B.C. under the BC Wildlife Act. Exotic foxes like Fennec Foxes are also not allowed as pets under Controlled Alien Species Regulations.

The BC SPCA does not support keeping wild or exotic animals as pets, due to their unique physical and emotional needs. These animals often suffer in care because of their specialized needs.

Read more about the BC Government’s Controlled Alien Species Regulations.

Raccoons may establish a toilet or “latrine” site in backyards. Raccoons are not carriers of rabies in B.C., but their poop may contain raccoon roundworm eggs that can be dangerous to people and pets. Try using motion-sensor lights or sprinklers to prevent raccoons from using your backyard as a toilet.

To clean raccoon poop on your property:

Avoid direct contact with the feces, and wear gloves and a face mask for protection. Scoop the feces up using a plastic bag or shovel, close tightly and place in the garbage.

Use heat to kill roundworm eggs:

- Use boiling water to destroy any roundworm eggs on every surface or item that touched the feces.

- If you can’t use boiling water on the surface or item, using a 10% bleach solution will dislodge roundworm eggs so they can be rinsed away.

- Flaming with a propane torch is also effective, but use with caution to avoid injury, damage, or starting a fire. Do not attempt to flame any surfaces that could melt or catch fire, and check the regulations of your local fire department and municipality in advance.

More information on cleaning raccoon latrines (CDC).

If you need help getting a raccoon out of your house, call an AnimalKind company. For more information on managing raccoons, read or print our best practices (PDF).

When young crows are learning how to fly, they may spend up to a week on the ground building up their flight muscles. The parents will watch from close by and try to protect their young – sometimes dive-bombing people who get too close. Unless the young crow is hurt or in a dangerous place, you can leave the crow alone.

If you watch and listen, you’ll hear the young crows begging for food and see the parents come down to care for them.

Avoid walking near the fledgling crow, keep pets on a leash and warn others in the area. If you have to pass through, carry an open umbrella as an extra barrier. Don’t worry – the parents will leave you alone as soon the young crow can fly away with them.

Read more about why crows attack and what you can do to protect yourself.

Bats are the only wild carrier of rabies in B.C. and should never be touched or directly handled. Rabies can spread through just a drop of a bat’s saliva. Vaccinate your pet to protect them from contracting rabies.

If a bat has had any skin contact with a person, the bat must be euthanized and tested for rabies. If a bat has had contact with a pet, the bat may be sent for rabies testing. Contact your doctor, veterinarian or local public health authority immediately in cases of contact with a bat. Learn more about rabies transmission.

Bat populations are in decline, and injured bats can be rehabilitated. Call your local wildlife rehabilitator or our Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice on safely containing bats.

Help bats by also watching out for signs of White-Nose Syndrome (WNS). White-Nose Syndrome is a fungal disease that has been devastating bat populations across North America. The fungus grows on the nose and bodies of infected bats during hibernation and causes them to wake and use valuable energy at a time when they should be conserving it. White-Nose Syndrome has not been observed in B.C. yet, but the fungus that causes it was detected in the Grand Forks area in 2023.

Between November 1 and May 31, White-Nose Syndrome can be detected on dead bats if they are infected. Help detect White-Nose Syndrome by reporting dead bats and unusual winter bat activity to the BC Community Bat Program at 1-855-9BC-BATS (922-2287) or by email at info@bcbats.ca.

To learn more about coexisting with bats, read the BC SPCA’s best practices for bats.

Small deceased wild animals found on private property can be buried or bagged and put in the garbage. Do not touch dead wildlife with your bare hands – use disposable gloves or a tool – and never put a dead animal in compost or green bins. For larger animals on private property, it may be your responsibility to dispose of them, and you may need to contact a waste removal company for help. Contact your local municipality for more information.

For deceased animals found on public land, contact your local animal control or public works office for removal.

If there is more than one deceased animal in the same area, or if you suspect disease, consult the provincial government website for reporting instructions for a variety of species including amphibians, bats, birds, small mammals, large mammals, and marine mammals.

Dead bird reporting

Birds are susceptible to diseases such as West Nile virus and avian influenza. To monitor bird health in British Columbia, reports of sick and dead wild birds are of interest to federal and provincial government agencies. The B.C. Wild Bird Mortality Investigation Protocol & Avian Influenza Surveillance Program coordinates the surveillance of diseases and deaths throughout the province.

Report sightings of dead wild birds by reading the Wild Bird Mortality & Avian Influenza Surveillance Program (PDF) information sheet and calling 1-866-431-BIRD (2473).

Sick or injured birds should be taken to a permitted wildlife rehabilitation centre as soon as possible. Read more about how to rescue a wild animal. Still need help? Contact your local wildlife rehabilitation centre or the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice about how to help sick or injured birds.

Learn more about HPAI and ways to reduce transmission in your own backyard.

Bird bands

If you find a dead bird with a band or coloured markers, record the letters and numbers and contact the Wild Bird Mortality & Avian Influenza Surveillance Program at 1-866-431-BIRD (2473).

The North American Bird Banding Program collects information on the distribution and movement of species to help wildlife scientists monitor and conserve migratory bird populations. You can contribute by also reporting the band number online at reportband.gov or by calling 1-800-327-BAND (2263) toll-free to leave a message.

Pigeons are not banded as part of the North American Bird Banding Program. A pigeon with a leg band is likely a domestic pigeon and their band will have letters representing a racing association who can help to get in touch with the owner. Learn more about bird banding.

Don’t feed the wildlife. The BC SPCA is generally opposed to the feeding of wild animals. Wild animals suffer when they get used to eating human food instead of their natural diet. When people feed wildlife, the animals also lose their healthy fear of people. This increases their chances of being injured or killed. Some municipalities have bylaws against feeding wildlife.

Keep wildlife healthy and wild! Don’t share your food, garbage, compost or litter. Read or print our brochure: Don’t Feed the Animals (PDF).

What about birds? Read more about feeding birds and hummingbird feeders.

What is the rabies virus?

Rabies is a viral disease of warm-blooded animals that can be transmitted to humans. It is caused by a virus of the Rhabdoviridae family, which attacks the central nervous system and eventually affects the brain. Rabies is almost always fatal in animals and people once symptoms occur.

How is rabies transmitted between animals and humans?

The virus is transmitted through close contact with the saliva of infected animals, most often by a bite or scratch. It can also be transmitted by licks on broken skin or mucous membranes, such as those in the eyes, nasal cavity or mouth. In very rare cases, person-to-person transmission has occurred when saliva droplets became aerial. Bat bites can inflict small wounds and go unnoticed.

Who is at risk of being infected by rabies?

Bats are the only known wild carrier of rabies in B.C. Like cats and dogs, raccoons, coyotes, skunks, farm animals, and any other mammals are capable of contracting the rabies virus, but are not considered carriers in B.C.

In other provinces like Ontario, raccoons, coyotes, skunks and foxes are wild carriers of rabies. In B.C., however, the only carrier of rabies is bats; no raccoons or skunks in B.C. have ever transmitted rabies.

How common is rabies in bats in B.C.?

It is estimated that one per cent of bats in the wild in B.C. carry rabies. In June 2004, four skunks in Stanley Park in Vancouver tested positive for the rabies virus. However, it was discovered that they all carried the bat strain of rabies; likely they had all been in contact with a rabid bat.

Cases of human rabies infection in Canada

In the past 25 years, five people in Canada have died of rabies infection: one in Quebec (2000), one in Alberta (2007), one in Ontario (2012) and two in British Columbia (2003 and 2019). In the Ontario case, rabies exposure occurred outside the country. These were the first cases of human rabies in Canada since 1985.

The most likely source of infection for both B.C. individuals was unrecognized bat exposure. Without wound cleansing or post-exposure vaccinations, the potential incidence of rabies in exposed humans can be very high.

Does my pet need a rabies vaccine?

Dogs and cats account for fewer than five per cent of all animal rabies cases in Canada. However, rabies presents a serious public health risk, and even indoor pets could come in contact with a bat. Some pets also need the vaccine for travel. Ask your vet whether your pet should be vaccinated.

What if my pet brings a bat home?

If your pet brings home a bat, you should take your pet to a veterinarian. If the bat is available, your vet may send it for rabies testing. Additionally, your vet may vaccinate your pet against rabies and/or ask you to keep your pet in your home for several months to see if they develop signs of rabies.

If any person in your household has touched a bat with bare skin, seek medical attention from a doctor or local public health unit immediately.

What will happen to the bat?

The bat may be euthanized and sent for testing. As of April 1, 2014, CFIA veterinary inspectors are no longer involved in species collection activities. However, the CFIA continues to perform and cover the cost for rabies laboratory testing involving domestic and wild animals and humans. This is vital as once the symptoms of rabies (flu-like including fever, headache and fatigue, progressing to gastrointestinal and central nervous system problems) start to appear, there is no treatment and the disease is almost always fatal. However, wound cleansing and immunizations, done as soon as possible after suspected contact with an animal, can prevent the onset of rabies in virtually 100 per cent of exposures.

What to do if there has been contact with a bat

Bat-to-person contact?

If treatment is given promptly after being exposed to (any bare skin contact) or bitten by a bat, the illness may be prevented by taking the following actions:

- Immediately wash the wound or exposed surface with soap and water for 10 minutes and cover the area with a clean bandage.

- Remove any clothing that may have been contaminated.

- Immediately call your doctor and local health authority for advice.

Bat-to-pet contact?

Please contact your veterinarian to have your pet vaccinated and discuss whether a period of isolation/observation is required for your pet. If the bat is available, your veterinarian may send it for rabies testing.

Found an injured bat?

No matter how injured, a bat should never be touched with bare hands. Please refrain from nudging or picking the bat up.

Injured bats can be rehabilitated by professionals able to take the necessary precautions against rabies transmission. Call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice on safely containing bats and finding a wildlife rehabilitator.

It is typically illegal to disturb a bird’s nest with eggs or chicks inside. The best solution is to wait a few weeks until the babies grow up. If there is a nest in an area that causes problems (above a building entrance, in a vent) you may need a permit from Environment Canada to move the nest legally.

For species-specific information on managing birds, read our best practices. If you have more questions about a nest of birds, call the BC SPCA Animal Helpline at 1-855-622-7722 for advice.

Under provincial and federal law, it is illegal to keep a wild animal, as designated under the BC Wildlife Act, as a pet. Very rarely, the provincial government issues permits for the personal possession of wild animals.

The BC SPCA does not support keeping wild or exotic animals as pets due to their unique physical and emotional needs. Both types of animals – those found wild in Canada and those exotic in Canada but wild to other countries – will suffer in care because of their specialized needs.

Under provincial law, it is illegal to keep certain dangerous exotic animals like tigers, primates or crocodiles as pets. Many cities also have exotic animal bylaws that make it illegal to keep some or all exotic pets. Check with your local municipality for a list of banned exotic animals.

Read more about exotic animals and the law.

If you are concerned about someone owning a wild or exotic animal illegally, please contact the Conservation Officer 24-hour RAPP line at 1-877-952-7277.